What Happened to Jim That Ended Any Hope of Playing Football Again?

Development of the NFL Player

Creating an NFL player: from "lowest" to "superman."

The earliest NFL players were everymen.

Playing rules prohibited near substitutions, and then they played both offensive and defensive positions, on every downwards. Meager pay and a sport struggling for popularity meant players worked other jobs and the league struggled to attract talent. Physically, players were bigger, heavier and stronger than the average man, just not astronomically so.

Their lives didn't circumduct around the game. It was common for players to "task in" for weekend contests, which didn't let for practice time with their teams. Their pay fabricated them "professional" past definition, but with a laxity to the term that would not apply today.

The game and the players changed over time as the rules changed, and equally the league became more competitive, popular and prosperous.

Today, only football game'southward elite players get to the NFL, and they are very well-compensated: the average contract at the start of the 2017 flavor was $ii.25 meg. Competition for roster spots is fierce, with fewer than 1 percentage of all college football game players earning a roster mail at the game'southward highest level.

Nigh players are bigger and stronger — particularly offensive and defensive linemen, whose size and weight surpass the average man'due south. And players are more specialized by position, with physical attributes and customized training rituals unique to their roles.

Hall of Famer Wilbur "Pete" Henry, aka "Fats," was 1 of the NFL'due south largest and most dominant linemen in the 1920s at v feet 11 inches and 245 pounds, just would be dwarfed by nowadays-day players such as half-dozen pes 6 inch, 313-pound New Orleans offensive tackle Ryan Ramczyk. (Pro Football Hall of Fame) (AP Photograph/Jeff Bottari)

As players progress from high school through the pros, they're increasingly supported, coached and counseled by trainers, nutritionists and medical staff that prepare them for peak functioning on gameday and help them recover from injury. Their training and preparation often continues through the offseason.

NFL players are professionals in every sense of the discussion, well-paid and well-trained students of the game whose lives revolve effectually football game. The league, in turn, surrounds them with resources to aid them get the all-time they can exist. Merely information technology all had to outset somewhere — in this case, with a homo named William "Pudge" Heffelfinger.

The Birth of the Playing Professional

On Nov. 12, 1892, Heffelfinger received $500 in cash for playing in a football game game. There may take been others before him, but a document unearthed by thePro Football Hall of Fameabout eighty years later provided the first irrefutable show of a person beingness paid to play. Heffelfinger posthumously earned the status every bit the state'due south first professional football player.

At half dozen feet three inches tall and 200 pounds, William "Pudge" Heffelfinger "was especially large for that era and towered over his opponents," according to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

At the time, all football game players were supposed to be amateurs — many of them playing for teams created past the athletic clubs that sprang up across the land after the Civil War. With the competition between clubs becoming more intense, many tried to circumvent the restriction by finding jobs for their stars, awarding players expensive trophies or watches that they could pawn, or doubling their expense money. Only none of them paid cash, at to the lowest degree not openly.

A Nov. 12, 1892, contest betwixt Pittsburgh-area rivals the Allegheny Able-bodied Association and the Pittsburgh Athletic Club changed everything. As the game approached, both teams were determined to beef up their squads. Heffelfinger — a low-salaried railroad office employee in Omaha, Beak. — became 1 of their targets.

The clubs had good reason to bid for his services. As a football game All-American at Yale from 1888 to 1891, Heffelfinger was considered ane of the sport's best linemen. According to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, "his size immune him to wreak havoc on opposing lines, where it was said he would typically take out two to three players at a time." He helped lead Yale to two undefeated and two one-loss seasons (including one incredible undefeated campaign in which it outscored its opponents 698-0).

Heffelfinger's post-college status, however, was typical for football's rag-tag days. He went to work at the railroad, simply continued playing for independent teams. In the weeks earlier the Allegheny-Pittsburgh competition, he took a leave of absence from the job to take part in a six-game tour of the East with the Chicago Athletic Association, which used the expense-money method to attract players.

The Pittsburgh Athletic Lodge scouted 1 of those games and, according to a Pittsburgh Press story at the time, offered Heffelfinger $250 to play for them on Nov. 12. Allegheny offered him $500. The star played for Allegheny and earned his go on by forcing a bollix, scooping it up and racing for a touchdown — the game's merely score.

Allegheny did non admit to paying Heffelfinger at the time, but the Hall of Fame discovered a club expense sheet that shows the $500 transaction. Information technology calls the document "pro football's birth document."

Allegheny shelled out $250 for a unlike role player in a November. 19 game, and for the 1893 flavour, it signed three players to contracts that promised them $l per game. The pay-to-play model had arrived.

A Famous Football Family and The Dawn of a League

The payments, withal, were not high enough to induce dramatic modify. In the early 1900s, without the developmental pipeline that exists today, pro football players still came from nigh anywhere. For many, their forcefulness came from hard labor, non football-specific preparation or college play.

The half dozen Nesser brothers, known for their overpowering play, averaged more than 210 pounds in an era where the average professional lineman weighed 180. (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

I of the game's toughest and most popular teams of that era emerged from the sandlots and railroad yards of Columbus, Ohio, where six outsized brothers congenital their musculus through backbreaking piece of work and played football during tiffin breaks.

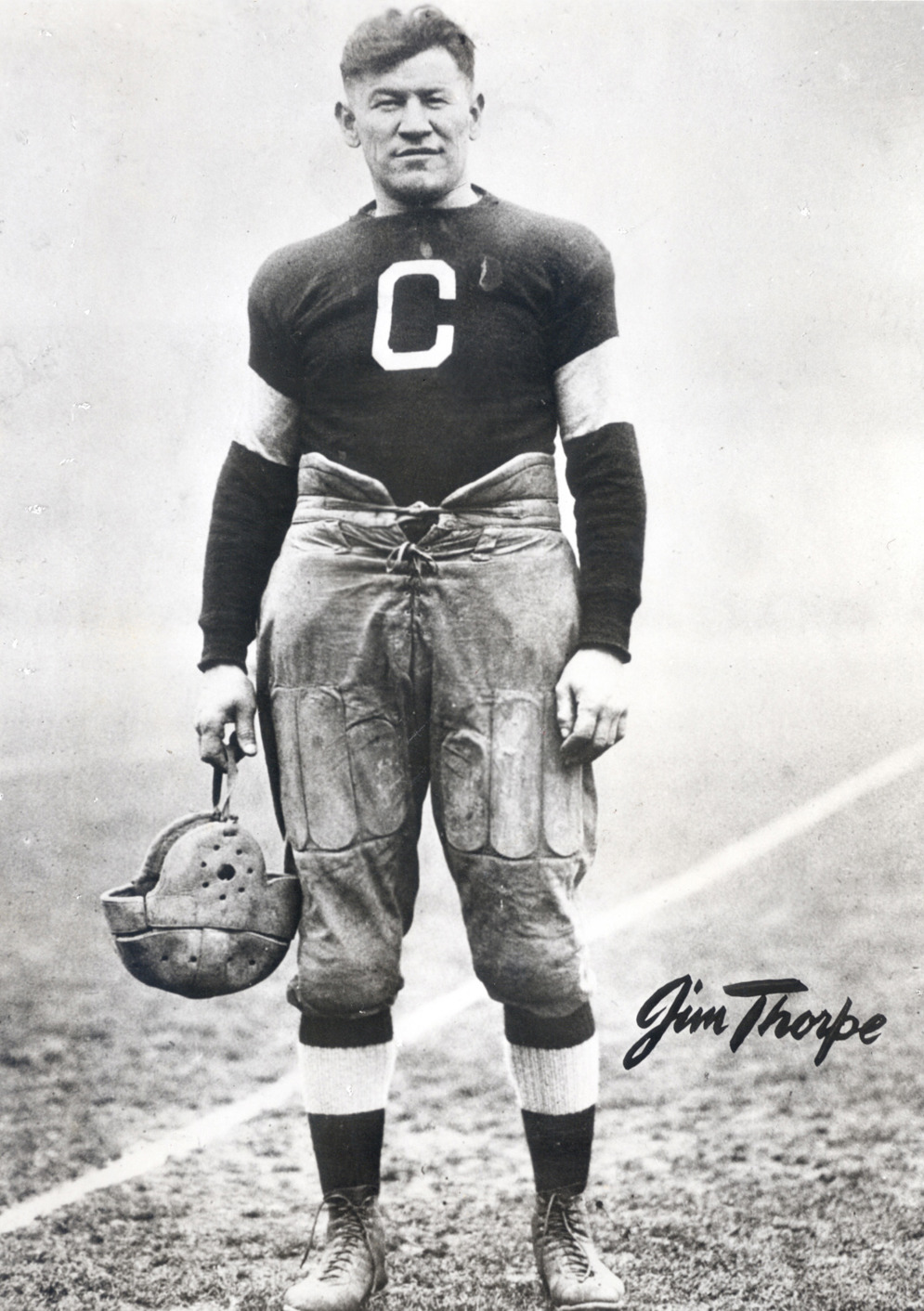

Jim Thorpe, vi feet 1 inch alpine and about 200 pounds, combined speed with bruising power equally a halfback. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

Joe Carr formed the Columbus Panhandles in 1907, with the Nesser brothers equally the nucleus. Renowned for its bruising play, the team would become a big road game draw as the "near famous football game family in the country," the Hall of Fame says.

Jim Thorpe — the 1912 Olympics decathlon and pentathlon aureate medalist — became an fifty-fifty bigger attraction for the fledgling sport than the Nessers.

Signed by the County Bulldogs in 1915 for the then-princely sum of $250 a game, Thorpe already had proven his football game mettle by earning first-team All-American honors in 1909 and 1910 while playing higher football for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. He also played professional person baseball. Having such an elite and high-profile athlete additional the sport's prestige.

In 1920, both the Panhandles and Bulldogs became lease members of the 14-team American Professional Football game Association, which inverse its name to the National Football League in 1922.

The league appointed Thorpe as its kickoff president. Carr became its 2d in 1921 and held the position for eighteen years; equally one of his commencement actions, he established a standard player contract modeled on the ane used in baseball.

A New Era for the Player

The germination of the league would be looked back on as a seminal moment for pro football, of course, but also for players. Over fourth dimension, the league would provide a structure for thespian recruitment and development, every bit well as the rules and conditions that would shape how the game is played and who plays it.

By 1920, college football had begun to demonstrate its superiority every bit a source for pro players, completing a shift that had begun with Thorpe in 1915.

"The day when a whole team of rugged sandlotters could compete on an equal footing with college-trained pros was over," Professional Football Researchers Association (PFRA) members Bob Braunwart and Bob Carroll wrote in 1979. "Many sandlotters withal played useful roles with practiced pro teams, but the key men had earned varsity messages at colleges."

College graduates, even so, were not flocking to the new league, and many saw it as a step down from higher football game.

Harold "Scarlet" Grange, a superstar at the University of Illinois, elevated the NFL's prestige and popularity — and negotiated a healthy cut of the profit — when he signed upward for a wildly popular barnstorming tour with the Chicago Bears in 1925. (AP Photo)

The NFL's 1925 signing of Harold "Cherry" Grange, a University of Illinois star famous for his long touchdown runs, marked a turning point in that thinking. Grange knew the league wanted him as a gate allure, so he retained an amanuensis — theater possessor C.C. Pyle — and negotiated a deal with the Chicago Bears late in the 1925 season for fifty per centum of the receipts on an 18-day, 10-game barnstorming tour.

Exhausted and injured, Grange barely completed the tour, simply he and Pyle reportedly made $150,000, and the team toured again from belatedly December through January in Florida and California. A severe genu injury in 1927 reduced Grange's touch as a player, especially on offense, just his touch on the pro game's prestige and popularity remained.

In 1926, the NFL'Due south Duluth Eskimos signed Ernie Nevers, a Stanford Academy All-American and 1925 Rose Bowl hero. In 1927, the league'southward Cleveland Bulldogs signed Benny Friedman, a University of Michigan star considered the greatest passer of his mean solar day. Both would become headliners for the league, receiving top billing over the squad's they played for.

Simply signings like those of Grange, Nevers and Friedman were notable in that they remained a relative rarity. The NFL was not attracting and retaining the country's top talent. In its early days, the league was regional and unstable, with a steady churn of teams and low pay.

Even in 1930, some standouts preferred to play with independent teams in the towns in which they worked rather than moving to join the NFL. And many college players eschewed pro play altogether, using their educations to move into higher-paying professions.

In 1936, the first NFL draft began to formalize the path from college to the pros. By i count, just 24 of the 81 drafted players signed contracts with the NFL — a reflection of the league's inferior status and low pay levels.

The number one pick in that draft, Jay Berwanger, turned down $125-$150 per game and never even received a response to his request for $25,000 over 2 years. He took a job equally a cream rubber salesman instead.

University of Chicago star Jay Berwanger won the first Heisman Bays and was the first overall selection in the 1936 draft, only he chose a job selling foam rubber over playing in the NFL; he would later launch a successful manufacturing business organisation. (Pro Football game Hall of Fame)

The first draft was but partially successful, simply information technology established a method for bringing higher players into the game and one for distributing talent fairly amongst teams. That would become invaluable equally the league matured.

The NFL matured significantly during the 1930s and '40s. Information technology farther distinguished itself from the college game past adopting its own set of rules — many of which additional the offense — and improving the quality of play on the field.

Equally the league improved, so did its level of talent. The path to the NFL became clearer every bit independent pro clubs disappeared. Other leagues would claiming the NFL — the American Football League (AFL) in the 1960s past far the almost successful and influential. Simply the AFL merged with the NFL, as did the All-America Football game Conference (AAFC) in 1950, and the others faded away. The NFL became the premier place to play.

Integration and Specialization

The years during and immediately after World State of war 2 brought ii large player-related developments. One expanded the talent pool; the other inverse the type of talent that teams would seek.

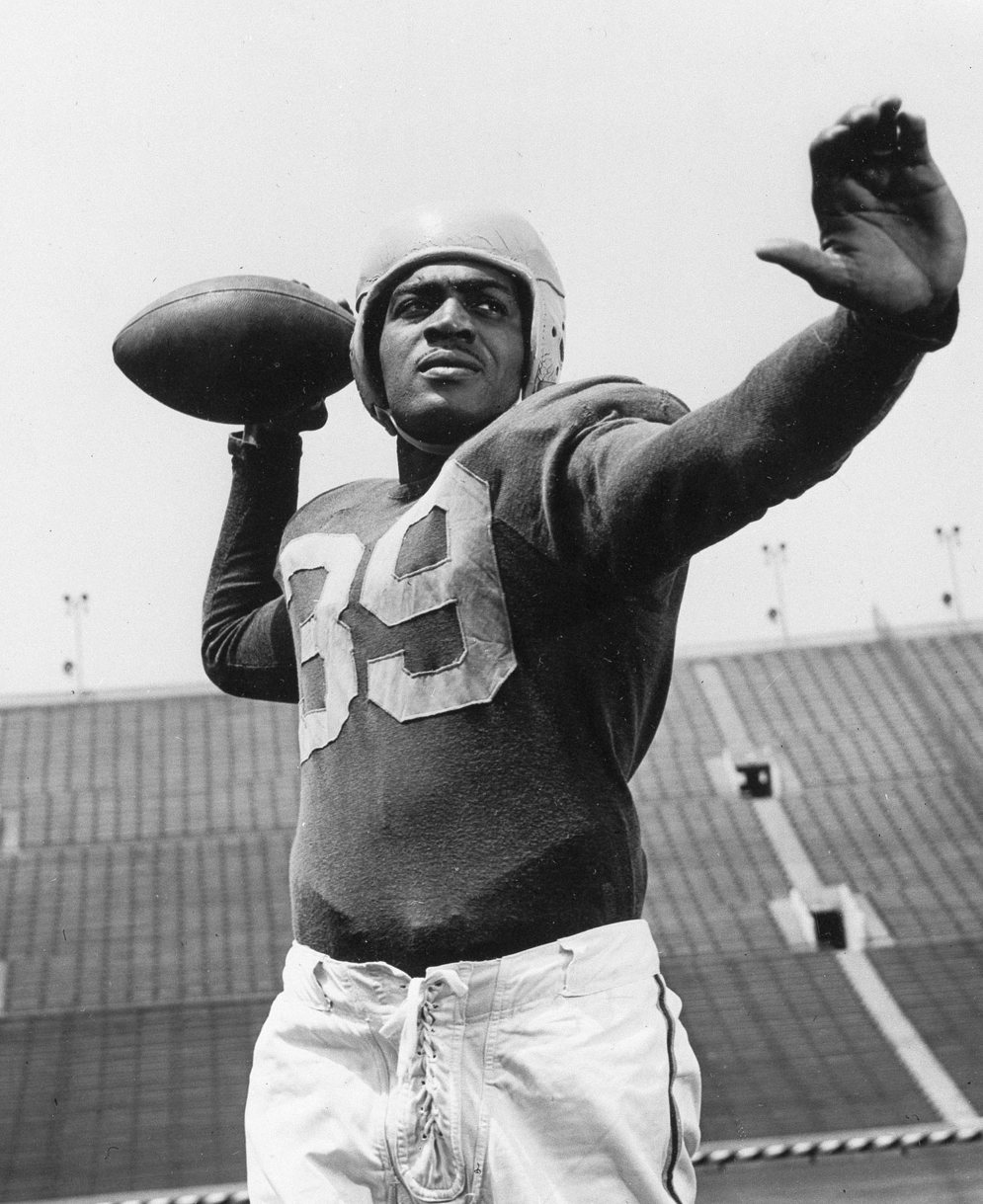

African American players returned to the NFL. While several had played in the league's early on days, the league effectively banned African Americans from 1933 to 1945.

That finally ended in 1946 — a year before Jackie Robinson broke pro baseball game'due south color barrier — with the Los Angeles Rams' signing of Kenny Washington and Woody Strode.

That same twelvemonth, Paul Brown, coach and part-owner of its Cleveland franchise in the upstart AAFC, signed African American standouts Neb Willis and Marion Motley.

Leading up to its 1950 merger with the NFL, the AAFC would actually integrate faster than the NFL.

The other big change involved a rule.

In the 1920s though the early 1940s, most players were similar in size because substitutions were mostly prohibited. Players were largely interchangeable and played every play — oft playing multiple positions — on offense and defense force. Fifty-fifty kickers played every downward at other positions.

Kenny Washington of the Los Angeles Rams, seen on Sept. 3, 1946. (AP Photo)

With America's immature men serving in World War Ii, the NFL faced thespian shortages and fiscal struggles. Only the league's response would forever alter the game and the make upwards of the men who play it.

The shortage of fit players forced the NFL to change its rules to allow free substitutions. The league tried to re-implement its restrictions afterwards the war, just substitutions proved then popular that it lifted its restrictions permanently in 1949.

Players no longer needed to be able to play both offense and defense and could even take the field for just a scattering of plays per game. That meant that, for example, coaches could apply modest and speedy receivers to energize their offenses, since those players would not need the size required to play defense.

Garo Yepremian's Botched Field Goal

Punters and kickers no longer had to cake, tackle, run, catch or pass. A club could keep a histrion primarily to return punts and kickoffs.

Over time, teams' roster sizes grew, abetting the trend. Teams went from 16 "active list" players available for play in every game in 1925 to 30 by 1938, and forty by 1964. Since the 2011 season, each squad tin identify 46 agile and seven inactive players before each game. More than roster spots meant coaches could beget to reserve spots for specialists.

Specialization was gradual equally coaches adopted new strategies to have advantage of players with unique concrete attributes and skills — all in the proper noun of trying to gain an edge on their opponents.

Increasingly, kickers became more than ane-dimensional. Witness Miami Dolphin Garo Yepremian — 5 feet 8 inches and 175 pounds — when he tried to salvage a botched field goal try in his squad'southward xiv-seven Super Bowl VI victory over the Washington Commanders That play was not his finest moment, but his kicking prowess made him worthy of a roster spot — Yepremian was named to the NFL All-Decade for the 1970s. Similar any specialist, kickers needed to excel just at the job they were hired to do.

Football every bit a Career

Cleveland Browns guard Chuck Noll (a futurity Hall of Famer for his coaching triumphs with Pittsburgh) was a salesman for Trojan Freight Lines in the offseason. (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

The belatedly 1950s saw an explosion in football's popularity, especially after the 1958 Championship Game between the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants, which is still considered by some equally "the greatest game ever played." Role player pay, all the same, was ho-hum to catch up.

A Cleveland Plain Dealer story told the story of how virtually all Browns players worked second jobs in the early on 1960s during the 6-month off-flavour to supplement their income.

Future Hall of Fame defensive finish Willie Davis taught students mechanical drawing in 1961. Linebacker Jim Houston, a first-circular pick in the 1960 draft, opened an insurance and financial planning company. Guard Chuck Noll (future Hall of Famer for his coaching triumphs with Pittsburgh) was a salesman for Trojan Freight Lines.

Off-season conditioning was not the norm, because players spent it working and pursuing other interests.

Past the early on 1970s, football had overtaken baseball as the state'south favorite spectator sport. Television set contracts, sold-out stadiums, merchandising and sponsorship deals ensured an abundant, steady flow of cash.

In the 1970s, '80s and '90s, the growth of the NFL Players Association — first formed in 1956 with Cleveland players every bit a nucleus — gave players more than say in how their profession developed and contributed to a big boost in salaries. So, too, did the always-ascension profitability and popularity of the game.

Today's NFL players spend off seasons in rigorous workout, exercise and nutritional programs preparing for the next flavour. Clubs work with the players to provide sophisticated training techniques, equipment and medical expertise year-round.

Future NFL stars now beginning with youth football game and play through high schoolhouse and college, all with support systems in identify to develop players at every level. Peak athletes may make information technology to the NFL, and most players are often more fit and prepared for the professional game than e'er earlier.

Sized and Specialized

Players take grown in many ways over the past three decades — in professionalism, earnings, specialization, size and strength.

High school quarterbacks learn to read defenses, and defenses use line stunts and rush packages. Specialization takes hold early. Many major college programs accept adopted pro-style offensive schemes creating players more than prepared to adjust to the NFL game.

Increased specialization in the NFL and the development of offensive and defensive coaching strategies accept led to new optimal trunk types for each position, with customized conditioning and nutritional programs to match.

NFL Players at about positions are bigger and stronger than their predecessors, merely sizes and torso styles have diverged — sometimes dramatically — based on the demands of their roles. As data journalist Noah Veltman noted after crunching the numbers on NFL player meridian and weight over time, "nowadays, if you're vi foot 3 inches and 280 pounds, you're too big for most skill positions and too pocket-sized to play line."

One recent analysis of average player weights by position, using data from NFL.com for each player on 2013 rosters, found a range from 193 pounds for cornerbacks to 315 for offensive guards. (The difference in average heights, while not every bit dramatic, ranged from 5 foot 11 inches for running backs and cornerbacks to half dozen human foot 5 inches for offensive tackles.

Nowhere is the deviation more evident than on the offensive and defensive lines.

In the early 1980s, Washington Commanders line coach Joe Bugel told Joe Jacoby, a 6 foot 7 inch, 275-pound offensive tackle at the Academy of Louisville, that he had a chance to brand it in the NFL — but merely if he got bigger.

Washington Commanders offensive tackle Joe Jacoby was a giant among men, but he actually had to majority upwards to brand it in the NFL. (AP Photograph/Al Messerschmidt)

With training, Jacoby increased his bench press from 300 to 400 pounds, put on thirty pounds and increased his quickness in the 40-yard dash to v seconds flat. He fabricated the squad every bit an undrafted free amanuensis in 1981 and became part of one of the almost famous and ascendant offensive lines in NFL history — the "Hogs" — which powered the squad to 3 Super Bowl titles.

But in terms of size, the "Hogs" wouldn't look that imposing today. Even Jacoby — so imposing that one writer said of him, "Andre the Giant wears his mitt-me-downs" — wouldn't stand out. Past 2013, the median weight for NFL guards and tackles had reached 310 pounds, according to ane assay. That means over half weigh more Jacoby did.

One of the smallest Hogs — Hall of Famer Russ Grimm — stood six feet 3 inches and weighed 273 pounds. Today, he would be one of the league'southward smallest guards.

For defensive ends, the need for speed and agility to blitz the quarterback may mitigate some of the size increase. Ends averaged 283 pounds and 6 feet iv inches tall, the assay of 2013 NFL rosters found.

But defensive tackles, responsible for shutting down an opponents running game, averaged 6 human foot 3 and 310 pounds. Compare that to NFL legends like Mean Joe Greene, the vi pes 4, 275-pound tackle for the Pittsburgh Steelers from 1969-81, or Dallas Cowboy Hall-of-Famer Randy White, who played the position for the Dallas Cowboys from 1975-1988 at 6 feet 4 inches, and 257 pounds.

The impression that players at every position are much bigger and stronger than previous generations is not always true. Sometimes the ideal torso type for today'south game is actually smaller. Consider the running back.

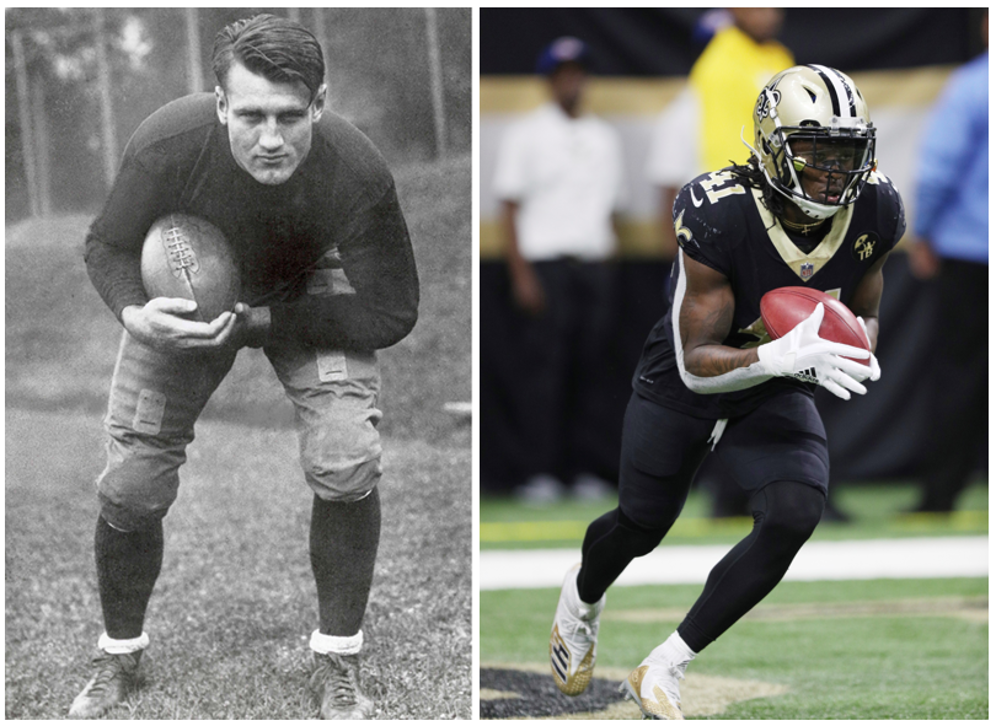

Bronko Nagurski, the ball carrier who became the NFL'south symbol of power football game during the 1930s, stood 6 feet two inches tall and weighed 226 pounds. His force and size helped him plow through would-be tacklers.

Running backs today boilerplate only shorter than vi feet, and 215 pounds. On those terms alone, Nagurski would not be outmatched. But today's runners use their size to hide behind the massive linemen blocking in front of them, and spend countless hours in training to develop the dispatch and lower body strength to speed through holes and fight for extra yardage.

At 6 anxiety 2 inches and 226 pounds, 1930s Hall of Fame running back Bronko Nagurski was bigger and heavier than many of today's stars, like New Orleans' Alvin Kamara (5-10, 215), but he likely did non share some of their specialized skills, strengths and abilities. (Pro Football game Hall of Fame) (Margaret Bowles via AP)

Quarterbacks do not necessarily stand up taller either. Stars from different generations of play — Sammy Baugh (vi feet ii inches), Bart Starr (6 feet 1 inch) and Joe Montana (6 feet 2 inches) — would not take to look upward at most of today's stars.

But like the majority of today'southward players, body mass is greater — perchance a beneficiary of training and a reflection of the need to withstand hits from those bigger defensive linemen. The boilerplate weight has risen to about 224 — more than than 20 pounds above the playing weights of Baugh, Starr and Montana.

The Professional Player

Simply beyond size, players are different today because of their football environment.

Their support organization through youth leagues, high schools and college — from the leagues and schools themselves and NFL-sponsored events and actor evolution programs — is unprecedented. Relieved of the need to play on both sides of the ball on every downwards, they have honed their skills at specific positions. Given the time and resources, they have maximized their fitness and become greater students of the game.

Professionals now in every sense of the word, they are the best of the best, a specialized elite, continuing to drag the game.

Source: https://operations.nfl.com/inside-football-ops/players-legends/evolution-of-the-nfl-player/

0 Response to "What Happened to Jim That Ended Any Hope of Playing Football Again?"

Post a Comment